I came across this advance notice

One day conference held in Manchester,

Wednesday 20 June 2012

The event will be held in Manchester Metropolitan University

As the centenary of the Great War approaches and it slips from first-hand experience, shelves on military history in high-street bookshops testify to the misty-eyed mythical appeal it continues to have for many. This conference forestalls the coming public history bonanza by concentrating on the under-researched responses to the crisis from the regions and localities of Britain. Was there a common national response to unprecedented events or did strong local and regional identities cause significant variations?

This day conference will bring together twenty papers from scholars working on regional issues in the Great War and its aftermath. Strands include:

• Recruiting, volunteering and conscription

• Local patriotisms

• Agriculture, food and rural life

• Commemoration and religion

• Community and home front

Speakers will include:

Keith Grieves, Nick Mansfield, Helen McCartney

Professors Chris Williams and Karen Hunt

More details and application form at http://www.mcrh.mmu.ac.uk/confer/gw/index.htm

Picture; taken from website origin Cambridge Collection, Cambridge Central Library

Saturday, 31 December 2011

Letter from Viareggio .......... another day

The queue at the local bakery shop below our balcony shows no sign of going down. It is Sunday in Viareggio, or more accurately on the Via XX Settembre and it is just before 11. Ours is a narrow busy street, with people on bikes, noisy scooters and that blasted alarm from the school just round the corner. Odd said Simone that the alarm should keep going in the school holidays and joked it must be the only place that school children want to break into a school in the holidays.

But I digress, the line of shoppers has vanished but still there are small groups hanging around, renewing friendships, catching up on a week’s news or just watching the life on the street pass by. They spill out over the pavement into the road making it difficult for the cars to navigate around them. Surprisingly all of this is performed without road rage in a matter of fact way.

Sunday is a traditional time to visit family and many of the cakes bought from our shop will be taken as gifts. And as I write a rather striking woman in her 50s passes with a box wrapped in gold paper destined no doubt to be the centre piece of a visit. Just behind her follow an even statelier couple. She dressed immaculately walking hand in hand with a tall elderly man slowly as befitting two who have more years behind them than ahead.

It is a beautiful morning, the sky is a bright blue and the church behind the apartments adds to the atmosphere with a regular peal of bells. Earlier in the morning we had mass relayed to all the surrounding streets.

Rosa and Tina were up early, buying at the fish market and now the apartment is full of the smell of cooking fish. Nothing quite prepares you for the sight of fresh fish only hours from when they were pulled from the sea. I am introduced to flat broad ones, a few even odder looking ones and plenty of large shell specimens one of which still slowly moves its legs.

At home I doubt we would have the variety or the odd looking ones. Here what you get is what you are offered; the sea after all does not deliver to order. And the same applies to vegetables and fruit. Yesterday’s melon still came with the earth clinging to its sides while the tomatoes, peppers and aubergines were all sizes and all shapes. I only hope that it is a long time before we get regular sized, perfectly formed produce that are on offer at home.

Viareggio is a city and commune in Tuscany

Picture; the market in Viareggio, from the collection of Andrew Simpson

But I digress, the line of shoppers has vanished but still there are small groups hanging around, renewing friendships, catching up on a week’s news or just watching the life on the street pass by. They spill out over the pavement into the road making it difficult for the cars to navigate around them. Surprisingly all of this is performed without road rage in a matter of fact way.

Sunday is a traditional time to visit family and many of the cakes bought from our shop will be taken as gifts. And as I write a rather striking woman in her 50s passes with a box wrapped in gold paper destined no doubt to be the centre piece of a visit. Just behind her follow an even statelier couple. She dressed immaculately walking hand in hand with a tall elderly man slowly as befitting two who have more years behind them than ahead.

It is a beautiful morning, the sky is a bright blue and the church behind the apartments adds to the atmosphere with a regular peal of bells. Earlier in the morning we had mass relayed to all the surrounding streets.

Rosa and Tina were up early, buying at the fish market and now the apartment is full of the smell of cooking fish. Nothing quite prepares you for the sight of fresh fish only hours from when they were pulled from the sea. I am introduced to flat broad ones, a few even odder looking ones and plenty of large shell specimens one of which still slowly moves its legs.

At home I doubt we would have the variety or the odd looking ones. Here what you get is what you are offered; the sea after all does not deliver to order. And the same applies to vegetables and fruit. Yesterday’s melon still came with the earth clinging to its sides while the tomatoes, peppers and aubergines were all sizes and all shapes. I only hope that it is a long time before we get regular sized, perfectly formed produce that are on offer at home.

Viareggio is a city and commune in Tuscany

Picture; the market in Viareggio, from the collection of Andrew Simpson

Friday, 30 December 2011

Chasing a shadow .............. uncovering the war record of a British Home Child Part One

Now I have written quite extensively about British Home Children and my great uncle. He was one of the 100,000 British children who were sent to Canada to start a new life by organisations dedicated to saving the poor.

His early life was not an easy one. He was in care from the age of four, knew little about his father and narrowly escaped a term in a naval boot camp, preferring to cross the Atlantic in the May of 1914 and settle on a farm in Canada.

This would have been a challenge to any urban child and so it was with my great uncle who did not adjust to his new life. Instead after three placements which all proved unsuccessful he ran away in the August of 1915 and joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

Like many young men he lied about his age and unlike many he discarded his given name and adopted a new one, and as if to further distance himself from his old life, he claimed both parents were dead, and gave as his next of kin his aunt.

This should have made searching for him difficult. But the Library and Archives Canada which is similar to our own National Archives proved a goldmine of detail, they can be accessed at www.collectionscanada.gc.ca

Here were his Attestation papers which were the first official document a young recruit signed. For the historian and the family researcher they are the first port of call in summoning up a young man’s military career. Here can be found biographical details, physical description and names and addresses of next of kin.

These are valuable enough but in the case of my great uncle give an insight into what he was thinking when he enlisted and how he wanted to be seen.

Clearly lying about his age got him into the army and changing his name ensured the organisation that brought him over to Canada could not track him.

I am not sure why he lied about his parents. I guess because he had last seen his father when he was 4 and it was easy to assume him dead. But his mother he knew to be alive, having briefly lived with her a year before. Perhaps it was the circumstances of him being taken back into care because his mother “was unfit to have control” and given this it was easy to draw a line under family ties. But then having decided against a factious brother he named his real aunt citing her correct address.

The Canadian war archives have not suffered from damage from German bombing in the Second World War and so are complete, which meant it was possible to follow his career from enlistment and training camp in England to his time on the Western Front.

His personal records do not give any detail beyond his court martial’s, his units and his eventual demob. But sitting alongside these records are the War Diaries which each regiment had to complete. They describe the day to day actions of the unit both under fire and at rest which means it is possible to gain an insight into what men like my great uncle had to endure.

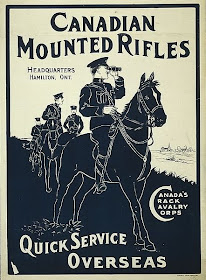

Picture; Recruitment poster for the Canadian Mounted Rifles, from Library and Archives Canada

His early life was not an easy one. He was in care from the age of four, knew little about his father and narrowly escaped a term in a naval boot camp, preferring to cross the Atlantic in the May of 1914 and settle on a farm in Canada.

This would have been a challenge to any urban child and so it was with my great uncle who did not adjust to his new life. Instead after three placements which all proved unsuccessful he ran away in the August of 1915 and joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

Like many young men he lied about his age and unlike many he discarded his given name and adopted a new one, and as if to further distance himself from his old life, he claimed both parents were dead, and gave as his next of kin his aunt.

This should have made searching for him difficult. But the Library and Archives Canada which is similar to our own National Archives proved a goldmine of detail, they can be accessed at www.collectionscanada.gc.ca

Here were his Attestation papers which were the first official document a young recruit signed. For the historian and the family researcher they are the first port of call in summoning up a young man’s military career. Here can be found biographical details, physical description and names and addresses of next of kin.

These are valuable enough but in the case of my great uncle give an insight into what he was thinking when he enlisted and how he wanted to be seen.

Clearly lying about his age got him into the army and changing his name ensured the organisation that brought him over to Canada could not track him.

I am not sure why he lied about his parents. I guess because he had last seen his father when he was 4 and it was easy to assume him dead. But his mother he knew to be alive, having briefly lived with her a year before. Perhaps it was the circumstances of him being taken back into care because his mother “was unfit to have control” and given this it was easy to draw a line under family ties. But then having decided against a factious brother he named his real aunt citing her correct address.

The Canadian war archives have not suffered from damage from German bombing in the Second World War and so are complete, which meant it was possible to follow his career from enlistment and training camp in England to his time on the Western Front.

His personal records do not give any detail beyond his court martial’s, his units and his eventual demob. But sitting alongside these records are the War Diaries which each regiment had to complete. They describe the day to day actions of the unit both under fire and at rest which means it is possible to gain an insight into what men like my great uncle had to endure.

Picture; Recruitment poster for the Canadian Mounted Rifles, from Library and Archives Canada

Letter from Viareggio

Florence was all we had hoped for. True there were times when the sheer ebb and flow of nationalities all keen on soaking up some of Florentine history proved challenging but we accepted we were tourists, took the sightseeing bus and followed the guide book.

Now I have always been snooty about a sightseeing bus and guide book, never wanting to admit that I was a tourist, which was both silly and arrogant. Silly because I missed out on what there was to know, and arrogant because I didn’t know much about the cities we visited. So Tina bought the book and got seats on the bus and Florence became more comprehensible as a result.

But all adventures can only really begin with a train journey. Aeroplanes and coaches are a poor substitute for a fast powerful train and an unknown railway station. First there is the station, smaller and more intimate than an airport, but still with all the promise of distant places.

Viareggio station is a business work a like place. It can’t claim to have the majesty of the great London termini, or the graceful sweep of the train shed at York. Nor has it that stark modernism of the Termini in Rome. Viareggio is a concrete block which fronts 8 simple platforms, but it has trains and that makes it magic.

We were there for 7.30; the train to Florence takes an hour and half and leaves at 8.10 which gave us time for breakfast. Conetto with cream is a croissant with a sort of rich custard which with an expresso is a perfect way to start the day. You can get others filled with jam or chocolate and should not be confused with bombaloni which are donuts with the same fillings. We eat these on the platform watching as the first trains of the day pass through, south to Rome, and north to Florence and Pisa.

Italian trains are generally cleaner than ours. There are none of those discarded newspapers on seats and tables, nor the empty tins which roll up and down the aisle with the movement of the train. This has a lot to do with the team of cleaners who descend on the train as it arrives at the termini. With only a short window between its arrival and departure they move swiftly armed with bags and brooms. It is the sort of thing that did once happen at home which meant that if you were last off an inner city train you battled down the corridor trying not to impede their work with your suitcases.

The journey through the Italian countryside has its own rewards. There are the endless fields of maize and sunflowers in neat fields, cut through with streams and rivers while further away to the north small villages cling to the side of steep mountains, each with their own distinctive tall tower. I guess these were the refuges for a population plagued by war and marauding bands of mercenaries.

The heat of August is all too evident from the state of the rivers often shrunk to sluggish strips of water which have vacated great stretches of their original course.

We stop frequently and as the train heads north the fields give way to factories, and urban sprawl before arriving in Florence. We pass the sleek Euro Star Italia express train which should not be confused with the London to Paris Euro Star service. Just outside the station moving slowing out towards the south is the Silver Arrow and as we glide to a stop there beside us is the Red Arrow.

These are fast and elegant and will transport their passengers in style and comfort across Italy. They are the new Alta Velocitá trains which can take you from Milan to Rome in just 3½ hours compared to the old 5 hour service. Or from Milan to Bologne, Florence, Rome and onto Naples.

But it is the speed which more than anything impresses me. Milan to Florence in just 2 hours 10 minutes, Milan to Rome in under 4 and Rome to Naples in 1 hour 21 minutes. The Frecciarossa, or “Red Arrow,” is the fastest, with a maximum speed of 300-350KPH. The others are the Frecciargento, or Silver Arrow and the Frecciabianca or White Arrow which are slightly slower.

It’s not cheap a standard 2nd class seat on a train between Rome and Milan will cost around €70 one-way, and a 1st class ticket single will set you back more than €90. And the “flexi” tickets (which let you change trains without penalty) are even costlier – €111.70 for 1st class and €80.90 for 2nd class. But this seems reasonable set against our own high fares which are bewilderingly complicated.

By comparison our snail train cost us just over €13 each return. But it got us to Florence in comfort and the return journey had the bonus of being in a double decker train.

Picture; Viareggio station, the bar at 7.45 where all train journeys begin from the collection of Andrew Simpson

Thursday, 29 December 2011

100 years of one house in Chorlton ..................Part Six

I have been indulging my love of this house and telling its story and the people who lived in it set against the big and small changes to the way we lived through one hundred years.

The development of Chorlton as a pleasant dormitory suburb of Manchester had been going on a long time before we voted to be part of the city in 1904.

Some of the builders who took part in the building boom which attracted many newcomers were themselves new to the township. In the case of Joe Scott who features so much in the story of the house it was his father who had moved here from London just as new Chorlton was being developed.

But Joe preferred to build his houses in what had been the old rural centre of Chorlton and aimed at the rented market for small two up twp down properties with a kitchen extension. These dominate the little roads off Beech Road.

The site of his own house was well chosen. The front looked out onto the Rec and from the back he had an uninterrupted view across fields to the Brook and beyond towards Hardy Farm and the Mersey. As late as 1922 this was still true, although by then the new Chorltonville estate obscured the view of Hardy.

This land would not be seriously developed until the third decade of the 20th century when he began building semi-detached houses which in time would block even his view of the open land.

The house itself was a fine end terrace. The two ground floor living rooms had open fires with tiled surrounds and large wooden mantle pieces. The kitchen was small but had an open range which years later and in keeping with the fashion were replaced by a gas cooker and free standing units.

Now the Corporation had been supplying gas cookers for sale or rent from before the beginning of the 20th century and by the 1920s had show rooms on Deansgate and in Withington as well as travelling showrooms. It was keen to promote cookery demonstrations and collaborated with schools and the Women’s’ Guild.

I think we easily forget the degree to which the gas cooker transformed the lives of those who were involved in the day to day grind of household cooking. No more was there a need to bring in coal and keep clean an enormous range, for at the flick of a switch here was an abundant supply of fuel.

Our incorporation in to the city had many benefits, not least was that from 1906 the Corporation bought out the Stretford Gas Company and began supplying Manchester gas at a cheaper rate.

Joe however did not opt for gas lighting. There is no evidence in any of the houses in the terrace of gas lamps, unlike the newly built Chorltonville which constructed in the same year relied on gas. This I suppose shouldn’t surprise me given that Joe was already head of the game by offering for sale garages fitted with electricity.

Picture; advert for Joe Scott from the St Clements Church Bazaar for 1928, kindly supplied by Ida Bradshaw

The development of Chorlton as a pleasant dormitory suburb of Manchester had been going on a long time before we voted to be part of the city in 1904.

Some of the builders who took part in the building boom which attracted many newcomers were themselves new to the township. In the case of Joe Scott who features so much in the story of the house it was his father who had moved here from London just as new Chorlton was being developed.

But Joe preferred to build his houses in what had been the old rural centre of Chorlton and aimed at the rented market for small two up twp down properties with a kitchen extension. These dominate the little roads off Beech Road.

The site of his own house was well chosen. The front looked out onto the Rec and from the back he had an uninterrupted view across fields to the Brook and beyond towards Hardy Farm and the Mersey. As late as 1922 this was still true, although by then the new Chorltonville estate obscured the view of Hardy.

This land would not be seriously developed until the third decade of the 20th century when he began building semi-detached houses which in time would block even his view of the open land.

The house itself was a fine end terrace. The two ground floor living rooms had open fires with tiled surrounds and large wooden mantle pieces. The kitchen was small but had an open range which years later and in keeping with the fashion were replaced by a gas cooker and free standing units.

Now the Corporation had been supplying gas cookers for sale or rent from before the beginning of the 20th century and by the 1920s had show rooms on Deansgate and in Withington as well as travelling showrooms. It was keen to promote cookery demonstrations and collaborated with schools and the Women’s’ Guild.

I think we easily forget the degree to which the gas cooker transformed the lives of those who were involved in the day to day grind of household cooking. No more was there a need to bring in coal and keep clean an enormous range, for at the flick of a switch here was an abundant supply of fuel.

Our incorporation in to the city had many benefits, not least was that from 1906 the Corporation bought out the Stretford Gas Company and began supplying Manchester gas at a cheaper rate.

Joe however did not opt for gas lighting. There is no evidence in any of the houses in the terrace of gas lamps, unlike the newly built Chorltonville which constructed in the same year relied on gas. This I suppose shouldn’t surprise me given that Joe was already head of the game by offering for sale garages fitted with electricity.

Picture; advert for Joe Scott from the St Clements Church Bazaar for 1928, kindly supplied by Ida Bradshaw

Work, a romance, an illegitimate birth, marriage and seven more children in Whiteman's Yard

Wellington Street, the silk factory, a romance an illegitimate birth and marriage along with seven children and a life in Whiteman’s Yard.

I tried finding Smith’s Buildings on Wellington Street in Derby because it was here that one of my relatives lived before she got married. It was a daft idea really. She was there in 1861 when it was a close packed mix of houses and factories. Now it is just a stretch of car parks.

Maria Boot the mother of my great grandmother was born in 1845, brought up seven children and died in Whiteman’s Yard aged just 43.

She died of phthisis or tuberculosis which was a common enough disease in the 19th century and one that killed her father and mother. Like many who succumbed, she may well have been aware that the chronic cough; with its telltale signs of blood, the night sweats and weight loss were all signs that that she had been infected.

A poor diet, long hours of work and an absence of professional medical care made her vulnerable and like many of her generation she would have looked much older than she was.

No photograph has survived of Maria but I doubt we would have caught her smiling into the camera. This had less to do with being camera shy or a natural disposition to being stern but was a form of vanity. Smiling would reveal the row of missing and bad teeth which was the lot of so many of her class.

But once in the 1860s she would have been both youthful and I would like to think attractive. John Boot certainly thought so. He was a railway labourer and she a silk worker and they lived in the same house on Wellington Street.

Maria had worked as a silk winder which covered a number of different tasks, ranging from winding the silk on to the bobbins, cleaning the silk thread, to strengthening the filaments by a process called throwing. Much of the work was done by machines powered by overhead belts which in turn were connected to a drive powered by steam. These machines were spread out across the width of the mill floor.

Her job would have been to watch the bobbins on the machines, removing them when they filled with silk and replacing them with others and where necessary joining the ends of broken threads. It would have been repetitive and monotonous work, dominated by the clack thump and humming of the machines. Like as not she would have worked at either

the Mitchell and Slater silk mill or the Carrington Street Mill.

She was a boarder in the house that John Boot rented with his brother. Now I am at heart a romantic and I like to think that the two of them fell in love and planned when to marry. Alas as with so many love matches reality played out a little differently.

In 1862 Maria gave birth to her first son well away in Chesterfield while still single and it was not till 1864 that the two married. Perhaps it was out of consideration for decency that she gave Nelson Street as her residence on the marriage certificate.

I am less sure. Child birth outside marriage was less of a scandal than we like to think. In rural areas many brides were either pregnant when they stood in front of the altar, or had actually given birth before their marriage. In my own village there were sixty-seven illegitimate births during in seventy two years up to 1842 with some mothers having a second and even a third child. I doubt that it was any less so in the towns and cities.

Indeed one of Maria’s children did just that. Eliza was born in 1872 in Whiteman’s Yard fell in love with a young soldier and bore him five children. The children were born in Bedford, Birmingham Kent and lastly in the Derby Workhouse. The couple never married and sometime in 1902 they parted company. She came home to Derby with three children and pregnant with their fifth and he stayed in Kent where he married and had another five.

She went back to the same familiar patch living just streets away in Hope Street. This too has long gone and has also become a car park.

Picture; A silk machine,from A Day at Derby Silk Mill the Penny Magazine, 1843

I tried finding Smith’s Buildings on Wellington Street in Derby because it was here that one of my relatives lived before she got married. It was a daft idea really. She was there in 1861 when it was a close packed mix of houses and factories. Now it is just a stretch of car parks.

Maria Boot the mother of my great grandmother was born in 1845, brought up seven children and died in Whiteman’s Yard aged just 43.

She died of phthisis or tuberculosis which was a common enough disease in the 19th century and one that killed her father and mother. Like many who succumbed, she may well have been aware that the chronic cough; with its telltale signs of blood, the night sweats and weight loss were all signs that that she had been infected.

A poor diet, long hours of work and an absence of professional medical care made her vulnerable and like many of her generation she would have looked much older than she was.

No photograph has survived of Maria but I doubt we would have caught her smiling into the camera. This had less to do with being camera shy or a natural disposition to being stern but was a form of vanity. Smiling would reveal the row of missing and bad teeth which was the lot of so many of her class.

But once in the 1860s she would have been both youthful and I would like to think attractive. John Boot certainly thought so. He was a railway labourer and she a silk worker and they lived in the same house on Wellington Street.

Maria had worked as a silk winder which covered a number of different tasks, ranging from winding the silk on to the bobbins, cleaning the silk thread, to strengthening the filaments by a process called throwing. Much of the work was done by machines powered by overhead belts which in turn were connected to a drive powered by steam. These machines were spread out across the width of the mill floor.

Her job would have been to watch the bobbins on the machines, removing them when they filled with silk and replacing them with others and where necessary joining the ends of broken threads. It would have been repetitive and monotonous work, dominated by the clack thump and humming of the machines. Like as not she would have worked at either

the Mitchell and Slater silk mill or the Carrington Street Mill.

She was a boarder in the house that John Boot rented with his brother. Now I am at heart a romantic and I like to think that the two of them fell in love and planned when to marry. Alas as with so many love matches reality played out a little differently.

In 1862 Maria gave birth to her first son well away in Chesterfield while still single and it was not till 1864 that the two married. Perhaps it was out of consideration for decency that she gave Nelson Street as her residence on the marriage certificate.

I am less sure. Child birth outside marriage was less of a scandal than we like to think. In rural areas many brides were either pregnant when they stood in front of the altar, or had actually given birth before their marriage. In my own village there were sixty-seven illegitimate births during in seventy two years up to 1842 with some mothers having a second and even a third child. I doubt that it was any less so in the towns and cities.

Indeed one of Maria’s children did just that. Eliza was born in 1872 in Whiteman’s Yard fell in love with a young soldier and bore him five children. The children were born in Bedford, Birmingham Kent and lastly in the Derby Workhouse. The couple never married and sometime in 1902 they parted company. She came home to Derby with three children and pregnant with their fifth and he stayed in Kent where he married and had another five.

She went back to the same familiar patch living just streets away in Hope Street. This too has long gone and has also become a car park.

Picture; A silk machine,from A Day at Derby Silk Mill the Penny Magazine, 1843

Wednesday, 28 December 2011

Family illiteracy ............... the story of so many

Occasional stories of my family who lived in Derby in the mid 19th century

How easy we take writing our name. Even in an electronic age we still sign for things at the door, commit to a legal agreement and perhaps even sign a letter.

All of which made me think again about my family and how such a simple task was denied them.

In the summer of 1848 George Lowe died of TB. He was the grandfather of my grandmother which takes me back in an unbroken line to the mid nineteenth century. His death plunged a family already on the edge of poverty into real hardship. His wife Maria was just thirty one and she had five children the youngest of whom was just twelve months old.

No records have survived of how they coped, but I know she took in lodgers and the children all went into the textile industry as soon as they could. She had a series of jobs including collecting old linen and later in her later 50s as a charwoman.

Maria was illiterate as were all her daughters. They each left their mark instead of a signature on official documents. In the summer of 1848 Maria had left her mark on the death certificate of her husband and twenty-seven years later Mary her daughter also put a cross when registering the death of her mother Maria. All of the girls had each left their mark on their wedding certificates.

As shocking as this seems to us today it was not unusual. In 1840 when Maria was bringing up her daughters over 30% of men signed the marriage register with a mark.

The level of literacy was in part measured by the test of the marriage mark. The authors of the 1851 census on Education fell back on this simple test of how many people were able to sign their name on the marriage certificate as against those who put a cross or mark as a judge of the level of literacy. They were gratified that the number who put a cross had been falling but felt that it was still not good that well over a third of the population accented to marriage with a cross.

Here in Derby there were sixteen schools in the 1850s ranging from those catering for the well off to those aimed at catholic and Methodist families. But for the rest it would be a National School. These were church schools and provided elementary education for the children of the poor based on teaching of the church.

There were two of these not far from where Maria lived. On Edward Street was St Alkamund’s and on Curzon Street was St Werburgh’s on Curzon Street. What was offered was fairly basic ranging from reading writing and arithmetic and maybe languages, music, drawing and geography. The degree to which these were taught varied from subject to subject, and there was a gender split, so while almost all boys and girls were taught the ‘three Rs’, few studied modern languages. Boys were more likely to be taught mathematics than girls while more girls than boys were instructed in industrial occupations.

Nor were these gentle places of education. There was strict discipline and lessons were delivered with the help of monitors who were trained on the job, and much of this would focus on learning by rote. Standing outside the school the passerby would have heard the repetitive chanting as row by row the children repeated the prepared text. And if he had strayed inside, hanging from the walls around the room were embroidered verses extorting the virtues of thrift and hard work.

All of which I guess meant there was not much incentive for the girls to attend. And attendance was a problem, so while in the private sector the number of children attending on any particular day was over 90% in public schools which catered for the labouring classes the number it was much less.

For families like the Lowe’s the priority was bringing money into the house and so inspectors often commented that children were away from school and at work.

Not until 1870 was there universal provision for primary school education for working class children and even then it was still possible to gain exemption for even this limited schooling.

Listening to my mother’s experiences of school things had not changed over much by the 1920s. She had attended Traffic Street School as did my great grandmother sixties years earlier. Traffic Street School had been built in 1879 one of the new Board Schools of which many are still around today.

They were grand constructions, well built of brick, with high windows and were warm in winter and cool in summer. By comparison their replacements which went up in the 1950s may have looked better but had plenty of their own problems. The huge amounts of glass in these new wave schools made classrooms very hot in the summer but draughty in the winter and presented us with all the distractions due to being able to look out and see the passing world.

But as grand as Traffic School was it did not impress my family. Mother was regularly hit with an ebony ruler across her hands as an infant and during grandmother’s time attendance still only stood at 89%.

Still my mother came out of Traffic Street able to read and write and later wrote plays which were published. The descendants of the Lowe’s went on to University and some have become teachers. How easy it seems for one generation to make a living in a world denied to earlier members of their family.

Picture;the marriage mark of Maria Lowe in 1864, daughter of George and Maria 1864, from the collection of Andrew Simpson

How easy we take writing our name. Even in an electronic age we still sign for things at the door, commit to a legal agreement and perhaps even sign a letter.

All of which made me think again about my family and how such a simple task was denied them.

In the summer of 1848 George Lowe died of TB. He was the grandfather of my grandmother which takes me back in an unbroken line to the mid nineteenth century. His death plunged a family already on the edge of poverty into real hardship. His wife Maria was just thirty one and she had five children the youngest of whom was just twelve months old.

No records have survived of how they coped, but I know she took in lodgers and the children all went into the textile industry as soon as they could. She had a series of jobs including collecting old linen and later in her later 50s as a charwoman.

Maria was illiterate as were all her daughters. They each left their mark instead of a signature on official documents. In the summer of 1848 Maria had left her mark on the death certificate of her husband and twenty-seven years later Mary her daughter also put a cross when registering the death of her mother Maria. All of the girls had each left their mark on their wedding certificates.

As shocking as this seems to us today it was not unusual. In 1840 when Maria was bringing up her daughters over 30% of men signed the marriage register with a mark.

The level of literacy was in part measured by the test of the marriage mark. The authors of the 1851 census on Education fell back on this simple test of how many people were able to sign their name on the marriage certificate as against those who put a cross or mark as a judge of the level of literacy. They were gratified that the number who put a cross had been falling but felt that it was still not good that well over a third of the population accented to marriage with a cross.

Here in Derby there were sixteen schools in the 1850s ranging from those catering for the well off to those aimed at catholic and Methodist families. But for the rest it would be a National School. These were church schools and provided elementary education for the children of the poor based on teaching of the church.

There were two of these not far from where Maria lived. On Edward Street was St Alkamund’s and on Curzon Street was St Werburgh’s on Curzon Street. What was offered was fairly basic ranging from reading writing and arithmetic and maybe languages, music, drawing and geography. The degree to which these were taught varied from subject to subject, and there was a gender split, so while almost all boys and girls were taught the ‘three Rs’, few studied modern languages. Boys were more likely to be taught mathematics than girls while more girls than boys were instructed in industrial occupations.

Nor were these gentle places of education. There was strict discipline and lessons were delivered with the help of monitors who were trained on the job, and much of this would focus on learning by rote. Standing outside the school the passerby would have heard the repetitive chanting as row by row the children repeated the prepared text. And if he had strayed inside, hanging from the walls around the room were embroidered verses extorting the virtues of thrift and hard work.

All of which I guess meant there was not much incentive for the girls to attend. And attendance was a problem, so while in the private sector the number of children attending on any particular day was over 90% in public schools which catered for the labouring classes the number it was much less.

For families like the Lowe’s the priority was bringing money into the house and so inspectors often commented that children were away from school and at work.

Not until 1870 was there universal provision for primary school education for working class children and even then it was still possible to gain exemption for even this limited schooling.

Listening to my mother’s experiences of school things had not changed over much by the 1920s. She had attended Traffic Street School as did my great grandmother sixties years earlier. Traffic Street School had been built in 1879 one of the new Board Schools of which many are still around today.

They were grand constructions, well built of brick, with high windows and were warm in winter and cool in summer. By comparison their replacements which went up in the 1950s may have looked better but had plenty of their own problems. The huge amounts of glass in these new wave schools made classrooms very hot in the summer but draughty in the winter and presented us with all the distractions due to being able to look out and see the passing world.

But as grand as Traffic School was it did not impress my family. Mother was regularly hit with an ebony ruler across her hands as an infant and during grandmother’s time attendance still only stood at 89%.

Still my mother came out of Traffic Street able to read and write and later wrote plays which were published. The descendants of the Lowe’s went on to University and some have become teachers. How easy it seems for one generation to make a living in a world denied to earlier members of their family.

Picture;the marriage mark of Maria Lowe in 1864, daughter of George and Maria 1864, from the collection of Andrew Simpson

Harrogate, a Turkish Bath and a short history on the Romans

Yesterday we were in Harrogate visiting the Turkish Baths there. The notes tell me that we will move "from Steam Room which is the hot room with high levels of humidity, combined with eucalyptus infused steam, allows your body to relax, melts away tension in the muscles and opens pores helping to eliminate toxins.Then on to Tepidarium (Warm Room) where the

heat warms the body. This room prepares your body for the hotter Chamberswhich are the Calidarium (Hot Room) which is the intermediate heated room allowing the warmth to continue its therapeutic effect on the musculature and then the Laconium (hottest Room)

A more relaxing, less intense environment than a modern sauna, the Laconium purifies and detoxifies the body by opening the pores and stimulating the circulation. Lastly come the

Plunge Pool where you immerse your body in this cold invigorating pool. The change in temperature on the body improves circulation, flushes out toxins in the muscles and provides a toning effect and finally the Relaxation Room where you can spend 30 minutes cooling down in the elegant Frigidarium to round off the Turkish experience."

Now I have never been in a Turkish bath, but was an experience to savour, particularly as I have taught the story of the Roman bath house to countless children, and they are a direct descendant of the Roman bath house.

The Roman bath system was marvel, open to all and the grandest were like palaces. They were more than just a place to get clean, often including a gym and a library, they were a meeting place, to discuss the events of the day hatch plots and just relax.

Their remains can be found across the empire, from the fine homes of the rich to the garrisons of the military and even the humblest posting station offering accommodation to traveller on the road.

The finest were as you would expect in the great cities. The Baths of Caracalla were huge. Its central bath was 55.7 by 24 meters under three vaults reaching over 32 meters in the air. There was a doubl pool in the tepidarium, two gyms, and on the north side a huge roofless swimming pool with bronze mounted mirrors mounted overhead to direct sunlight into the chamber.

But I guess my favourites will always be the more humble ones, found in a modest villa or on outside one of the forts on the frontier. Simple affairs bit still keeping the idea of the Roman way of life going in some remote part of empire.

Picture; a reconstruction of the interior of the Baths of Caracalla 1899, from an article in Wikipedia, the Baths of Caracalla

Changing uses ................ the village school on the green

I had mixed feelings when I heard that the old school on the green was to be developed and turned into four homes.

It had been built in 1878 and replaced an older one dating from the 1840s. The conversion of any old building is a source for sadness, partly I guess because in its original form it has out lived its usefulness and will be lost to the community. In the case of the school this is particularly so given that I know people who attended it, have spoken to others who remember it as the venue for the Penny Savings Bank and hold one wonderful picture of the VE Day celebrations held inside in 1945.

But then as ever I am too romantic. After its closure as a school it had a number of uses and has been empty for years. I remember back in the '80s one discussion between friends to turn it into a restaurant which of course predated the transformation of Beech Road as a place of wine bars, cafes and restaurants by a decade. Rhona had the right idea but maybe we were ten years ahead of the game.

Still there was a danger that the place would if it remained empty begin to deteriorate and become a focus for vandalism. So at least this way the core of the building has been retained and has come back to life.

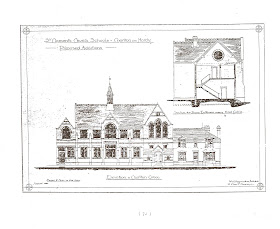

All of which is a way of introducing the map and picture of the proposed extension of the school in 1897. The plan was to add another floor and double the accommodation. It says much for the rapid growth of the township that this was necessary. As the authors of the report commented that the 1878 building “was thought suffice for many generations. However the abnormal growth of the parish within the last five years, has rendered a further enlargement imperative.”

The cost was estimated at £2,000 the bulk of which was expected to be raised through voluntary subscriptions. Today it seems rather odd that a public building like a school should depends on this form of funding but this was the norm, and both the two older National Schools and the three Methodist chapels and church along with Sunday schools had been built by such contributions.

Pictures; proposed plan and drawing for the enlargement of the village school, from the St Clements Bazaar Handbook, 1897, by kind permission of Ida Bradshaw

Tuesday, 27 December 2011

100 Years of one house in Chorlton .........Part Five

The continuing story of one house in Chorlton during the last hundred years.

Washing the family clothes was a tedious job and it may well be that Mary Ann paid to have the washing done.

Across the city there were 281 laundries some of which had more than one branch. Here in the township there were five, with another on Upper Chorlton Road, and another on Range Road as well as more in nearby Stretford, and Withington.

Of the five Chorlton ones, Mary was spoilt for choice, with Mrs Martha Keel on Beech Road, Miss Mary Jones at Ivy Cottage on Barlow Moor Road and the large Pasley Laundry on Crescent Road, now renamed Crossland Road. She may even have used Wing Sam & Co at Hastings Buildings on Manchester Road which was next to where they had lived in the spring of 1911.

Laundries are a measure not only of the size of a community but of their prosperity. Given the arduous nature of wash day it is not surprising that those who could afford to pay for the weekly washing to be cleaned did so. The population had doubled in the ten years before 1901 and the next decade saw an equal increase. The occupations of the residents of new Chorlton ranged from manufacturers, bank managers and solicitors to clerical and skilled workers. The very mix which is reflected in the large detached and semi detached houses stretching along Edge Lane and High Lane and the tall terraced properties radiating out from the station.

Here were the customers of our five laundries which in themselves were a mix. Yapp’s Laundry was big enough to have branches on Ashton Old Road, Chorlton on Medlock and in Whitefield and Stretford. Others like Wing Sam operated from one shop while Martha Keal’s premises on Beech Road was also the home of a her builder husband John. The biggest was the Pasley, later renamed the Queen and Pasley on Crescent Road. It opened in 1893, and at one point employed 50 staff.

All the washing machines were belt driven by a huge steam engine and were the first to install the “float-iron system” which consisted of the multiple roller pressing machine. This was 15 feet wide and 15 feet long and

“was a mass production ironing machine, with delicately poised rollers. You could put a shirt with pearl buttons on it and it wouldn’t leave a mark.”

Vans from the laundry would collect the washing and deliver it to the sorting office where each item would be marked, and classified into bins, before the loads were emptied into the ten washing machines. After being washed the clothes went through stages of being dried before being set out still slightly damp for the ironing and pressing and finally being resorted in the packing room and returned in the vans to the customers.

Whether Mary washed at home or used a laundry there would still have been much to do. It was after all a time before most families had a hover and sweeping dusting and general household cleaning was done the old way.

Picture; The Grange Laundry,Beech Road, Chorlton, c.1918

The Grange Laundry was opposite the smithy on Beech Road, Chorlton. c.1918.DPA/328/20 Courtesy of Greater Manchester County Record Office

Monday, 26 December 2011

The People’s History Museum.

I always get a real sense of the past when I visit The People’s History Museum. Here in a place dedicated to working men and women, are the stories of their struggle for the right to vote, to decent working conditions and above all the freedom to organize themselves in to trade unions, friendly societies and freely express their point of view.

The museum also carries out the important job of conserving banners of the trade union movement and has an extensive archive. I well remember standing in the old venue on Princess Street where the T.U.C. first met and held the minutes of the first meeting of the Labour Representation Committee soon to be renamed the Labour Party, and there at the bottom of the page was the signature of its first secretary, Ramsay MacDonald, who became the first Labour Prime Minister and less than a decade later split the Party by forming a National Government with the Conservatives and Liberals.

Along with the permanent displays there are plenty of temporary events and exhibitions. Running at preset is Picturing Politics – exploring the political poster in Britain which runs till June 2012. To keep up to date with the ongoing research on political posters, background information on some of the individual posters and the odd sneak preview of material, visit the blog written by Chris Burgess http://picturingpolitics.wordpress.com

The Museum is located at the bottom of Bridge Street, at the Left Bank, Spinningfields, http://www.phm.org.uk/

Picture; by Lawrence Beedle from the exhibition Exploring the political poster in Britain

Politics in the township ............ stories for the New Year

Coming soon to a blog you can read.

Who were the 31 men who could vote in the 1832 General Election?

Voter intimidation in the 1835 General Election

How farmers dominated the local Poor Law and Rates meetings

The fist local elections after Chorlton became part of the City of Manchester

Socialists on the Green

Picture; The election address of the Three Progessive Candidates on the 1904 Municpal Elections, from the collection of Lawrence Beedle

Sunday, 25 December 2011

British Home Children Poverty in the capital of a great Empire

Britain's slumdogs: The ragged and filthy East End children of just 100 years ago living a life of grime, Daily Mail, July 21st 2011

Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2017054/Britains-Slumdogs-The-ragged-filthy-East-London-children-just-100-years-ago-living-life-grime.html#ixzz1froCDU4T

Now the Daily Mail is not my newspaper of choice and the headline of the story on child poverty at the beginning of the 20th century is to say the least questionable. But the story and the accompanying pictures are a reminder that at this time of year there were those who did not and many who today will not share in a pleasant Christmas.

There are those who might question the motive behind the pictures, but it is as well to remember that in those early years of the 20th century we were a rich country even if not all shared in that wealth.

Between 1889 and 1910 the cost of food rose by 10 per cent and the cost of coal by 18 per cent. The life expectancy for working men was just 50 years of age and 54 for women, five per cent of children aged between 10 and 14 were already at work and the richest one percent held 70 percent of the wealth.

Picture; taken by photographer Horace Warner 100 years ago in Spitalfields in London’s East End, were later used by social campaigners to illustrate the plight of the poorest children in London.

Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2017054/Britains-Slumdogs-The-ragged-filthy-East-London-children-just-100-years-ago-living-life-grime.html#ixzz1froCDU4T

Now the Daily Mail is not my newspaper of choice and the headline of the story on child poverty at the beginning of the 20th century is to say the least questionable. But the story and the accompanying pictures are a reminder that at this time of year there were those who did not and many who today will not share in a pleasant Christmas.

There are those who might question the motive behind the pictures, but it is as well to remember that in those early years of the 20th century we were a rich country even if not all shared in that wealth.

Between 1889 and 1910 the cost of food rose by 10 per cent and the cost of coal by 18 per cent. The life expectancy for working men was just 50 years of age and 54 for women, five per cent of children aged between 10 and 14 were already at work and the richest one percent held 70 percent of the wealth.

Picture; taken by photographer Horace Warner 100 years ago in Spitalfields in London’s East End, were later used by social campaigners to illustrate the plight of the poorest children in London.

Saturday, 24 December 2011

100 Years of one house in Chorlton .........Part Four

This is the continuing story of one house in Chorlton, which Joe Scott the builder made for himself and his wife Mary Ann in 1911 http://chorltonhistory.blogspot.com/2011/12/100-years-of-one-house-in-chorlton-part.html.

I don’t know if Mary Ann had a servant but it is unlikely, so wash day was all down to her. This was both a time consuming activity and an ardours one.

The clothes would first be separated and placed in different wooden tubs to soak. The sheets and bed linen went in to one tub to soak in warm water and a little dissolved soda. The greasy clothes and dirtier things went into a second tub.

The clothes would then be taken out of the tub and rinsed and wrung before being washed, which involved applying carbolic soap to the garment and rubbing the material together in hot water. Alternatively she may have used a wash board.

Alternatively or additionally the washing was poked and agitated around in the hot soapy water with a wooden contraption called a dolly. There were some quite sophisticated ones with handles and 'stumpy 'legs' but it was also common just to use a wooden stick. This also served to lift the washing out of the water for rinsing, although wooden tongs were also used.

The clothes then had to be rinsed several times as well being put through the mangle which got rid of some of the dirty water. Finally they would be put in the copper of hot water and left for upwards of 90 minutes before being rinsed, first in hot water and finally again in cold water, and then rung out and hung out. Mrs Beeton writing over a half century earlier also advised putting the clothes into a canvas bag before putting in the copper to protect the clothes from the scum and sides of the copper. All this done and the clothes drying it only remained to wash the tubs and clean the copper.

Difficult as washday was, the volume of washing was nowhere near as much as today. Underwear was certainly washed frequently, but thick top clothes tended have to last with just dirty spots being sponged off. One sheet from each bed was washed weekly with the last week's top sheet becoming the next week's bottom sheet. The blankets were washed once a year in good drying weather in the summer.

Picture;

from a page of the first edition of Woman's Weekly November 1911

I don’t know if Mary Ann had a servant but it is unlikely, so wash day was all down to her. This was both a time consuming activity and an ardours one.

The clothes would first be separated and placed in different wooden tubs to soak. The sheets and bed linen went in to one tub to soak in warm water and a little dissolved soda. The greasy clothes and dirtier things went into a second tub.

The clothes would then be taken out of the tub and rinsed and wrung before being washed, which involved applying carbolic soap to the garment and rubbing the material together in hot water. Alternatively she may have used a wash board.

Alternatively or additionally the washing was poked and agitated around in the hot soapy water with a wooden contraption called a dolly. There were some quite sophisticated ones with handles and 'stumpy 'legs' but it was also common just to use a wooden stick. This also served to lift the washing out of the water for rinsing, although wooden tongs were also used.

The clothes then had to be rinsed several times as well being put through the mangle which got rid of some of the dirty water. Finally they would be put in the copper of hot water and left for upwards of 90 minutes before being rinsed, first in hot water and finally again in cold water, and then rung out and hung out. Mrs Beeton writing over a half century earlier also advised putting the clothes into a canvas bag before putting in the copper to protect the clothes from the scum and sides of the copper. All this done and the clothes drying it only remained to wash the tubs and clean the copper.

Difficult as washday was, the volume of washing was nowhere near as much as today. Underwear was certainly washed frequently, but thick top clothes tended have to last with just dirty spots being sponged off. One sheet from each bed was washed weekly with the last week's top sheet becoming the next week's bottom sheet. The blankets were washed once a year in good drying weather in the summer.

Picture;

from a page of the first edition of Woman's Weekly November 1911

Friday, 23 December 2011

Another time

There are those who harp back to a more innocent age, usually somewhere between their 5th and 15th birthdays. Before five it is all a bit of blur, and after 15 the many attractions of being on the threshold of adult life take you off on a roller coaster of grown up fun.

But those ten years were magic for most of us.

For me in the 1950s and early 60’s it a mix of playing on bomb sites, making Airfix models and being allowed out all day in the holidays. Often we would return just for something to eat and sometimes not even that. The milk was still delivered to the door and well into the middle of that decade by horse drawn cart, there was a newspaper in the letter box and boiled sweets were often the best you could expect.

All nostalgic tosh I know. It was also the decade of some very nasty wars including Korea and the many colonial conflicts the old European countries fought before granting independence to bits of their old empires. Polio still killed and maimed many children and thousands across Britain continued to live in sub standard dwellings which should have been demolished before the last world war.

But then you come across a picture which recreates that cosy world. Here are two of the Bailey family at the Didsbury show in 1947. Everything about the picture takes you back to a lost world. The school caps and short trousers, the horse drawn cart and the old spectacles.

Oliver Bailey commented on his picture "Have you forgotten the delights of a pennyworth (old money)of chips in the late forties? Also bear in find that shows like Didsbury brought the country to the city for a single day and there would be the equivalent of a concours d'elegance of horse drawn trade vehicles all immaculately painted and in one year the number of people was so great they broke open the fences to reduce the queuing. In days of rationing they were a flash of colour in a drab world"

Picture; from the collection of Oliver Bailey

Larkhill Place, Victorian Salford street museum

“Nostalgia isn’t what it used to be” nevertheless the past can be a cosy and comforting place. I was reminded of this recently when I was telling a friend about Larkhill Place. It’s a reproduction of a Victorian street in Salford Museum and Art Gallery.

Lark Hill Place was originally created in 1957 when many shops and houses in central Salford were being demolished to make way for new developments. Some of the shop fronts that were saved restored and interiors were added with f authentic objects, recreating the way they were used in Victorian times.

Here along the street are Mathew Tomlinson's General Store, a music shop, printers, pub, smithy and wheelwright as well as the chemist and druggist and dressmaker.

Today such theme places are more common than they were in 1957 and there is a danger that they present a sanitized interpretation of the past. The real noises smells and unwashed humanity are missing from the streets as is the dirt and ever present evidence of poverty.

But as an introduction particularly for children it is first rate. A good starting point is the museum’s own site at http://services.salford.gov.uk/larkhillplace/

Picture; the interior of one up one down cottage, in Larkhill Place, from the collection of Andrew Simpson

Lark Hill Place was originally created in 1957 when many shops and houses in central Salford were being demolished to make way for new developments. Some of the shop fronts that were saved restored and interiors were added with f authentic objects, recreating the way they were used in Victorian times.

Here along the street are Mathew Tomlinson's General Store, a music shop, printers, pub, smithy and wheelwright as well as the chemist and druggist and dressmaker.

Today such theme places are more common than they were in 1957 and there is a danger that they present a sanitized interpretation of the past. The real noises smells and unwashed humanity are missing from the streets as is the dirt and ever present evidence of poverty.

But as an introduction particularly for children it is first rate. A good starting point is the museum’s own site at http://services.salford.gov.uk/larkhillplace/

Picture; the interior of one up one down cottage, in Larkhill Place, from the collection of Andrew Simpson

The Postal Workers Strike of 1890 and an excellent Radio 4 series

There was a time when there could be as many as six postal deliveries and collections in a day. A service which allowed people to post a card in the morning and arrange to meet that afternoon or for day trippers at the sea side to alert the family for when they would be at home.

But of course there was a human dimension to such a service. A Commission of Inquiry heard evidence in 1896 of the extraordinary conditions some postmen endured. The work was heavy, their walks were long, and the hours were longer. Some had been known to walk 26 miles in a single day. Others worked split duties beginning at 6am and ending at 10pm, meaning they rarely saw their families. Some of the city offices were cold and damp in winter, where the staff had few amenities and only the most rudimentary toilet arrangements. Of course these were the worst-case scenarios, but there were other, more widely shared grievances such as low pay, stifling uniforms, minimal leave and a severe disciplinary code that included the awarding of the contentious and often divisive "good conduct stripes".*

Six years earlier these intolerable conditions led to the Postal Workers Strike of 1890 which can be read about at http://postalheritage.wordpress.com/2011/12/16/split-duties-in-the-1890s/

And appeared in the BBC Radio 4 series The People's Post: A Narrative History of the Post Office - 10. The Postal Worker's Strike, http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b0184vhd/The_Peoples_Post_A_Narrative_History_of_the_Post_Office_The_Postal_Workers_Strike/

*The Postal Workers Strike, from The British Postal Museum & Archive http://www.postalheritage.org.uk/page/peoplespost-strike

Picture, http://www.postalheritage.org.uk/page/peoplespost-strik

But of course there was a human dimension to such a service. A Commission of Inquiry heard evidence in 1896 of the extraordinary conditions some postmen endured. The work was heavy, their walks were long, and the hours were longer. Some had been known to walk 26 miles in a single day. Others worked split duties beginning at 6am and ending at 10pm, meaning they rarely saw their families. Some of the city offices were cold and damp in winter, where the staff had few amenities and only the most rudimentary toilet arrangements. Of course these were the worst-case scenarios, but there were other, more widely shared grievances such as low pay, stifling uniforms, minimal leave and a severe disciplinary code that included the awarding of the contentious and often divisive "good conduct stripes".*

Six years earlier these intolerable conditions led to the Postal Workers Strike of 1890 which can be read about at http://postalheritage.wordpress.com/2011/12/16/split-duties-in-the-1890s/

And appeared in the BBC Radio 4 series The People's Post: A Narrative History of the Post Office - 10. The Postal Worker's Strike, http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b0184vhd/The_Peoples_Post_A_Narrative_History_of_the_Post_Office_The_Postal_Workers_Strike/

*The Postal Workers Strike, from The British Postal Museum & Archive http://www.postalheritage.org.uk/page/peoplespost-strike

Picture, http://www.postalheritage.org.uk/page/peoplespost-strik

100 years of one house in Chorlton ................ Part Three

This is the continuing story of one house built in 1911 and set against the changes in Chorlton and the country over a century

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries Chorlton had expanded and with this expansion there came a clear shift of the centre of the township to the area around the station. So much so that there seemed to be a clear divide between these new communities close to the station and the older centre of population around the green and the Row. This divide was still there in the minds of some as late as the 1970s that could still be heard talking about old and new Chorlton. And it was also reflected in the positioning of the banks. All of these were close to the station while the Row and green had only the post office and the Penny Savings Bank which conducted its business once a week from the school house.

Historians of the township have drawn the link between these developments and the opening of the railway in Chorlton. But the coming of the railway is only part of the explanation for the housing boom, and those who sought to make the link between the train and new Chorlton have ignored the importance of water. Ours was a township which had relied on wells, ponds and water courses for all its water. Even in the 1840s and 50s these may have only just been an adequate and by the 1880s the wells were either polluted or drying up and the water courses disappearing into culverts.

The pivotal year was 1864. George Whitelegg had just finished building his four fine houses on High Lane known as Stockton Range in 1863 and had supplied them with indoor wells. But in the following year Manchester Corporation responding to a request from 17 rate payers had resolved “to authorise the laying of a [water] service Main in Edge Lane ........... for the supply of the houses included in the Schedule submitted and situate in Chorlton cum Hardy” The 3 inch main extended down Edge Lane, along St Clements Road to the Horse & Jockey. At the time there were only 11 houses along the course of the main, but during the next 13 years it was frequently extended till in 1877 a new 12 inch main was laid from Brooks Bar, along Manchester Road, Wilbraham Road and Edge Lane to Stretford which was as well as within another ten years the remaining wells were all but empty and becoming contaminated. Alongside which came plans to improve the sanitation of the township which led to the building of a sewage farm in 1879. It was as it had been for the ancients that the provision of clean water marked the moment a rural community looked towards becoming an urban one. This was in our case much advanced when in 1904 along with Withington and Didsbury we elected to join the city of Manchester.

Picture;Holland Road early 20th century still open land in the early

1890s, renamed Zetland Road from the collection of Tony Walker

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries Chorlton had expanded and with this expansion there came a clear shift of the centre of the township to the area around the station. So much so that there seemed to be a clear divide between these new communities close to the station and the older centre of population around the green and the Row. This divide was still there in the minds of some as late as the 1970s that could still be heard talking about old and new Chorlton. And it was also reflected in the positioning of the banks. All of these were close to the station while the Row and green had only the post office and the Penny Savings Bank which conducted its business once a week from the school house.

Historians of the township have drawn the link between these developments and the opening of the railway in Chorlton. But the coming of the railway is only part of the explanation for the housing boom, and those who sought to make the link between the train and new Chorlton have ignored the importance of water. Ours was a township which had relied on wells, ponds and water courses for all its water. Even in the 1840s and 50s these may have only just been an adequate and by the 1880s the wells were either polluted or drying up and the water courses disappearing into culverts.

The pivotal year was 1864. George Whitelegg had just finished building his four fine houses on High Lane known as Stockton Range in 1863 and had supplied them with indoor wells. But in the following year Manchester Corporation responding to a request from 17 rate payers had resolved “to authorise the laying of a [water] service Main in Edge Lane ........... for the supply of the houses included in the Schedule submitted and situate in Chorlton cum Hardy” The 3 inch main extended down Edge Lane, along St Clements Road to the Horse & Jockey. At the time there were only 11 houses along the course of the main, but during the next 13 years it was frequently extended till in 1877 a new 12 inch main was laid from Brooks Bar, along Manchester Road, Wilbraham Road and Edge Lane to Stretford which was as well as within another ten years the remaining wells were all but empty and becoming contaminated. Alongside which came plans to improve the sanitation of the township which led to the building of a sewage farm in 1879. It was as it had been for the ancients that the provision of clean water marked the moment a rural community looked towards becoming an urban one. This was in our case much advanced when in 1904 along with Withington and Didsbury we elected to join the city of Manchester.

Picture;Holland Road early 20th century still open land in the early

1890s, renamed Zetland Road from the collection of Tony Walker

Thursday, 22 December 2011

Practical and useful, manuals for the modest household

If you want to really understand a moment in time I think you can do no better than read their magazines. In this case it was the first edition of Woman’s Weekly which hit the newsstands on November 4th 1911 and reproduced last month. Then as now the magazine was designed to provide domestic advice from everything from how to make mistletoe lace to the problems of infant feeding.

Now such guides had existed since the beginning of the 19th century but I rather think Women’s Weekly was aimed at a new audience of modest means. It cost 1d and came out each week. It did not provide suggestions on how to deal with servants or how to stage a dinner party but instead catered for the woman who ran her own home and was expected to do everything, from making the family clothes to saving money. These women were those who had benefitted from educational reforms of the 1870s and were a new market to be exploited.

I guess many were aspiring to a better life and while Britain at the beginning of the 20th century was still a seriously unequal society the pages of Women’s Weekly offered a “practical and useful” way of improving their lives.

Picture: Souvenir edition of Woman’s Weekly 1911

100 years of one house in Chorlton .......... Part Two

This is the story of one house here in Chorlton.http://chorltonhistory.blogspot.com/2011/12/100-years-of-one-house-in-chorlton-part.html

Joe Scott built the house in 1911 and it was the first house the 23 year old builder lived in with his wife Mary Ann. It was part of a terrace of six and to mark it out as the home of the man who built it Joe gave it bay windows at the back, the only one of the six. His father and brothers were also in the building trade and it may be that they helped build it. His father Henry was a lath renderer or plasterer and I guess it would have been possible for him to have helped out here.

The Scott family are part of the history of the township. Henry had moved from London sometime in the 1870s, just as the housing boom had begun and he continued working into the twentieth century. Both of his sons became builders in their own right and Scott houses abound across the township.

There was also William Rochell from Yorkshire and later still Frederick Walker who also built homes for people. Just as the township attracted new people to live here it brought in the men who were going to build it.

By 1901 the brickworks had opened on Longford Road providing the material for lots of elegant villas and not so elegant terraces of brick houses which stretched out towards Martlege and back along new roads to the village.

In a few short years Scott, Rochelle and others were transforming the township, so much so that the Manchester Evening News commented that there was “great enterprises a foot and new roads are being monthly added to the local directory.”

Much of this new development was aimed at the clerical and artisan end of the market. As the same Evening News article said, “The clerk no less than the merchant must be catered for.” Many of these smaller terraced houses around Beech Road were Scott houses.

There was also the “Sandy Lane colony”, the three long new roads of Nicholas, Beresford and Newport and the “six shilling a week homes” on Hawthorne Road. All were modest four roomed houses, with a small front garden and back yard. In that respect the township remained a very down to earth place. There may well have been the grand houses which sat well back on Edge and High Lane but they were matched by those rows of small terraces.

Most of Scott’s houses were these smaller, modest houses in what was the old Chorlton. They were basic two up two downs with a kitchen tagged on and an outside lavatory and were built for rent. Later he began building semi detached houses on the remaining farmland off Beech Road and the green.

Picture;43-51 Beech Road, built by Joe Scott, Courtesy of Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives, Manchester City Councilm17663, taken in November 1958 by R.E. StanleyThe full collection of images can be viewed at http://www.manchester.gov.uk/info/448/archives_and_local_studies/326/photographs

Joe Scott built the house in 1911 and it was the first house the 23 year old builder lived in with his wife Mary Ann. It was part of a terrace of six and to mark it out as the home of the man who built it Joe gave it bay windows at the back, the only one of the six. His father and brothers were also in the building trade and it may be that they helped build it. His father Henry was a lath renderer or plasterer and I guess it would have been possible for him to have helped out here.

The Scott family are part of the history of the township. Henry had moved from London sometime in the 1870s, just as the housing boom had begun and he continued working into the twentieth century. Both of his sons became builders in their own right and Scott houses abound across the township.

There was also William Rochell from Yorkshire and later still Frederick Walker who also built homes for people. Just as the township attracted new people to live here it brought in the men who were going to build it.

By 1901 the brickworks had opened on Longford Road providing the material for lots of elegant villas and not so elegant terraces of brick houses which stretched out towards Martlege and back along new roads to the village.

In a few short years Scott, Rochelle and others were transforming the township, so much so that the Manchester Evening News commented that there was “great enterprises a foot and new roads are being monthly added to the local directory.”

Much of this new development was aimed at the clerical and artisan end of the market. As the same Evening News article said, “The clerk no less than the merchant must be catered for.” Many of these smaller terraced houses around Beech Road were Scott houses.

There was also the “Sandy Lane colony”, the three long new roads of Nicholas, Beresford and Newport and the “six shilling a week homes” on Hawthorne Road. All were modest four roomed houses, with a small front garden and back yard. In that respect the township remained a very down to earth place. There may well have been the grand houses which sat well back on Edge and High Lane but they were matched by those rows of small terraces.

Most of Scott’s houses were these smaller, modest houses in what was the old Chorlton. They were basic two up two downs with a kitchen tagged on and an outside lavatory and were built for rent. Later he began building semi detached houses on the remaining farmland off Beech Road and the green.

Picture;43-51 Beech Road, built by Joe Scott, Courtesy of Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives, Manchester City Councilm17663, taken in November 1958 by R.E. StanleyThe full collection of images can be viewed at http://www.manchester.gov.uk/info/448/archives_and_local_studies/326/photographs