It’s pretty difficult to picture a Chorlton which had just 325 people.

But in 1714 that was it. 325 individuals in 65 families and sixty years later this had only increased to 53. These 75 families inhabited 71 houses and like always most were situated around the parish church and out along the Row.*

There was another small concentration at Martledge** just north of the village and that was more or less it.

A few souls braved the isolation of Hardy beyond Chorlton Brook and a few more could be found dotted about the township.

Most would have lived in simple wattle and daub cottages, one room up and one down, while our farmers were beginning to build more substantial brick homes a few of which can still be seen around the green.

What is striking about our population in 1714 is its youthfulness. So a full 39% were under the age of 15, another 40% spanned the years from 16 to 49, leaving just 21% sliding slowly into old age.**

It was a picture which had not changed over much by 1841 when the first detailed census figures for the township can be analysed.

We were still a young community but when where a whole range of ailments could prove fatal.

Child mortality was at its highest amongst the very young in the warm weather when they were vulnerable to diarrhoeal infections and again in the late winter and spring from respiratory ailments.

And those who survived would have been visible in the cottage gardens, running errands, engaged in cleaning or just minding their siblings.

But generally this period in the story of the township is vague and what documents have survived either relate to the Barlow family of Barlow Hall or the Mosley’s up at Hough End. There is a tantalising reference to a dispute in the 17th century over rights to the extraction of marl on land around Longford Road but that is about it.

A few of our people are mentioned in settlement orders during the middle and late 18th century.

These were the documents which allowed a family a family to move into a community and were rigorously adhered to.

Anyone wishing to settle had to prove that they had the means to maintain a living or had connections with the township thus ensuring that at some future date they would not be a drain on the parish relief. And those who did settle without permission could be removed. In the course of the century there were those who obtained their settlement order and those who were removed because they had moved in without it.

One such family were the Crowther’s. Richard and Ellen from Manchester were granted settlement with their daughters Elizabeth aged 2 and Mary just six month in 1732.***

In 1765 when Mary was 32 she was subject to a removal order and ordered out of Stretford to Chorlton.

One possible reason might have been that as Mary was pregnant Stretford was unwilling either to support her or go to the trouble of issuing a Bastardy Order and pursuing the father to foot the bill for her care and that of the child.

The following year she buried a son called John, and went on to have three more children out of wedlock. These were James born in 1769, Martha in 1779 and Thomas in 1782. All three were baptised at St Clements and the parish may have had to support them.

Martha had a short life, having been baptised on March 28th 1779 she was buried on April 6th 1780.

Once back in Chorlton Mary stayed, living in one of two wattle and daub cottages on the Row,**** and died aged 90 in 1837. She is buried with her son Thomas who died the following year.

All of which has taken us a tad beyond the 18th century and is best left for another story

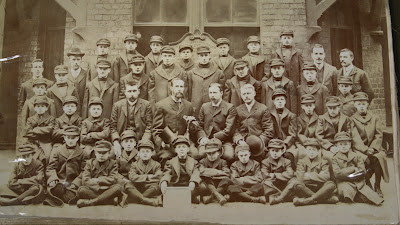

Picture;

map of Chorlton in 1786 from Yates’s map of Lancashire, courtesy of Digital Archives, http://www.digitalarchives.co.uk/ wattle and daub cottages, Bari Sparshot,

Mary Crowther’s grave from the collection of Andrew Simpson

*The Row is now Beech Road

**Martledge is the area stretching north from the Four Banks

**Booker, Rev John, A History of the Ancient Chapels of Didsbury & Chorlton, 1857

**** Lancashire County Records, QSP/1356/7

***** The cottages stood roughly where the Trevor Arms stands today