Now for those who don’t know Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt was one of the outstanding Radicals of the early 19th century.

He had campaigned for the reform of Parliament, called for universal suffrage, and demanded an end to child labour, and was imprisoned for two years for being at Peterloo.

Added to which in 1830 he was elected as the MP for Preston on a radical platform and went on to oppose the Reform Act because it didn’t go far enough.

And given such an illustrious commitment to reform and to Manchester, in 1842 he was commemorated by a monument, which four decades later was stolen.

The statue was not in one of the principle public places in the city but out on the edge, sandwiched between rows of working-class dwellings and in the shadow of a textile mill, and surrounded by an iron works, a chemical plant, and umpteen coal wharfs.

All of which I suppose was an appropriate spot for someone who had spent his adult life promoting equality and demanding a better deal for working people.

The monument was by all accounts an impressive thing.

The base was nearly six feet square and the plinth on which the monument rested was ten feet square.

There were spacious vaults underneath which were intended for “the remains of those who shall distinguish themselves in promoting the principles advocated by the late Henry Hunt”. *

And beneath the foundation stone were placed, the “memoirs of Henry Hunt, the history of the Peterloo massacre and his letters from Lancaster goal to the Reformers [along with] the placard announcing the ceremony, a copper plate likeness of Mr. Fergus O’Connor, and a copy of the address which was subsequently read to the meeting by Mr. Scholefield”.

Fergus O’Connor was one of the leaders of the Chartist movement and Mr. Scholefield, was the Rev. James Scholefield of the Every Street Chapel, and the monument was erected in the burial ground of the chapel.

Media coverage reported that “no less than 15,000 probably one half of whom were Chartists” [congregated] in Every Street and its neighbourhood”.

The address referred to the events at Peterloo and the decision “to perpetuate the memory of Henry Hunt, Esq, and of those who fell in that action, by erecting a public monument and thus show to future generations how the people of these times estimated sterling worth, and how they appreciate genuine patriotism”.

And that pretty much seems to be what happened over the next decade with leading members of the movement buried beside the monument.

In all five were interred in the grave which was “covered by a flat stone bearing the inscription “Names of the members of the Committee interred beneath. Peter Rothwell died 6th of September 1847, aged 78 years; George Hadfield, died 12th of January 1848, aged 59 years; George Exley, died 24th of January 1848, aged 79 years; Henry Parry Bennet, died 10th of November 1851, aged 65 years; James Wheeler, died 13th of September 1854, aged 63 years”. **

Sadly, the passage of time had not been kind to Mr. Hunt’s memorial and when the foundation stone was moved in 1888, the printed material had all but disintegrated and was in the words of an observer “rendered almost to pulp”, but there was a “medal of white metal” which was not mentioned in earlier accounts.

It had the figure of justice on one face and on the other a crown and a scroll bearing the words ‘Maga Charta, Liberty, Unity, Justice” and an inscription in the rim ‘Manchester Political Union, established August 16th, 1838’ ‘Universal suffrage, vote by ballot, annual Parliaments’”. **

And that leads me to the destruction of the monument, which was undertaken on the pretext that it was unsafe, although one visitor to the site at the time was less convinced that this was so.

Nevertheless, the contractor employed to make good the burial ground which had become neglected, broke the monument up and sold the stone for £3, which was then sold on again to “a man at Irlam-o’-the Height” who subsequently could not be traced.

This act of vandalism was condemned at the time and within days of its destruction an appeal was launched to raise money for a new monument.

There was some disagreement about what form the new memorial should take, with some arguing that the old site was unsuitable give the high wall that surrounded the old burial ground and its position on Every Street, “it had long been practically inaccessible for Manchester people” and a better alternative might be “a small marble tablet near the scene of Peterloo”.***

Today, little is left of the burial ground which is now an open piece of land surrounded by social housing and new build, but the outline of chapel has been preserved.

It was demolished in 1986 and a few of the original grave stones have been preserved.

Alas Mr. Hunt’s memorial is lost forever, although not as I first thought because of a vengeful act of conspiracy on the part anti-democratic forces but out of wanton greed compounded by neglect on the part of the family of the late Rev. Scholefield who had died in 1855.

Still I do have the names of the five interred beside the monument and they may yet bring forth fresh insights into Peterloo and that monument, in the centenary year of that massacre in St Peter’s Fields.

Location; Manchester

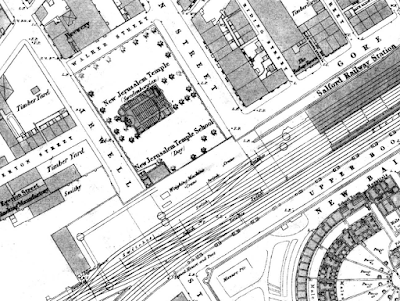

Pictures; Henry Hunt, circa. 1810, watercolour, by Adam Buck, 1759–1833, Peterloo, 1819 by Richard Carlile, m01563, Peterloo, 1819, m07589, the Round Chapel, 1959, m6868 , Courtesy of Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives, Manchester City Council, http://images.manchester.gov.uk/index.php?session=pass, the Round Chapel and burial ground, 1844, from the OS map of Manchester and Salford, 1842-44, and the Every Street burial ground, showing Mr. Hunt’s memorial, 1851, from Adshead map of Manchester, 1851, courtesy of Digital Archives Association, http://www.digitalarchives.co.uk/

*Monument to the late Henry Hunt, Manchester Guardian, March 27, 1842

**Henry Hunt’s Monument, Manchester Guardian October 6, 1888

***The Henry Hunt Memorial, The Manchester Guardian October 18, 1888

|

| Henry 'Orator' Hunt, circa 1820 |

Added to which in 1830 he was elected as the MP for Preston on a radical platform and went on to oppose the Reform Act because it didn’t go far enough.

And given such an illustrious commitment to reform and to Manchester, in 1842 he was commemorated by a monument, which four decades later was stolen.

The statue was not in one of the principle public places in the city but out on the edge, sandwiched between rows of working-class dwellings and in the shadow of a textile mill, and surrounded by an iron works, a chemical plant, and umpteen coal wharfs.

All of which I suppose was an appropriate spot for someone who had spent his adult life promoting equality and demanding a better deal for working people.

|

| The Round Chapel and burial ground, Every Street, 1844 |

The base was nearly six feet square and the plinth on which the monument rested was ten feet square.

There were spacious vaults underneath which were intended for “the remains of those who shall distinguish themselves in promoting the principles advocated by the late Henry Hunt”. *

And beneath the foundation stone were placed, the “memoirs of Henry Hunt, the history of the Peterloo massacre and his letters from Lancaster goal to the Reformers [along with] the placard announcing the ceremony, a copper plate likeness of Mr. Fergus O’Connor, and a copy of the address which was subsequently read to the meeting by Mr. Scholefield”.

Fergus O’Connor was one of the leaders of the Chartist movement and Mr. Scholefield, was the Rev. James Scholefield of the Every Street Chapel, and the monument was erected in the burial ground of the chapel.

Media coverage reported that “no less than 15,000 probably one half of whom were Chartists” [congregated] in Every Street and its neighbourhood”.

|

| The Round Chapel, burial ground and Mr. Hunt's monument, 1851 |

And that pretty much seems to be what happened over the next decade with leading members of the movement buried beside the monument.

In all five were interred in the grave which was “covered by a flat stone bearing the inscription “Names of the members of the Committee interred beneath. Peter Rothwell died 6th of September 1847, aged 78 years; George Hadfield, died 12th of January 1848, aged 59 years; George Exley, died 24th of January 1848, aged 79 years; Henry Parry Bennet, died 10th of November 1851, aged 65 years; James Wheeler, died 13th of September 1854, aged 63 years”. **

|

| Peterloo, 1819 |

It had the figure of justice on one face and on the other a crown and a scroll bearing the words ‘Maga Charta, Liberty, Unity, Justice” and an inscription in the rim ‘Manchester Political Union, established August 16th, 1838’ ‘Universal suffrage, vote by ballot, annual Parliaments’”. **

And that leads me to the destruction of the monument, which was undertaken on the pretext that it was unsafe, although one visitor to the site at the time was less convinced that this was so.

|

| Peterloo, 1819 |

This act of vandalism was condemned at the time and within days of its destruction an appeal was launched to raise money for a new monument.

There was some disagreement about what form the new memorial should take, with some arguing that the old site was unsuitable give the high wall that surrounded the old burial ground and its position on Every Street, “it had long been practically inaccessible for Manchester people” and a better alternative might be “a small marble tablet near the scene of Peterloo”.***

|

| The Round Chapel, 1959 |

It was demolished in 1986 and a few of the original grave stones have been preserved.

Alas Mr. Hunt’s memorial is lost forever, although not as I first thought because of a vengeful act of conspiracy on the part anti-democratic forces but out of wanton greed compounded by neglect on the part of the family of the late Rev. Scholefield who had died in 1855.

Still I do have the names of the five interred beside the monument and they may yet bring forth fresh insights into Peterloo and that monument, in the centenary year of that massacre in St Peter’s Fields.

Location; Manchester

Pictures; Henry Hunt, circa. 1810, watercolour, by Adam Buck, 1759–1833, Peterloo, 1819 by Richard Carlile, m01563, Peterloo, 1819, m07589, the Round Chapel, 1959, m6868 , Courtesy of Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives, Manchester City Council, http://images.manchester.gov.uk/index.php?session=pass, the Round Chapel and burial ground, 1844, from the OS map of Manchester and Salford, 1842-44, and the Every Street burial ground, showing Mr. Hunt’s memorial, 1851, from Adshead map of Manchester, 1851, courtesy of Digital Archives Association, http://www.digitalarchives.co.uk/

*Monument to the late Henry Hunt, Manchester Guardian, March 27, 1842

**Henry Hunt’s Monument, Manchester Guardian October 6, 1888

***The Henry Hunt Memorial, The Manchester Guardian October 18, 1888