Now it is easy to shudder and feel outrage at the accounts of housing conditions in the poor parts of Manchester in the first half of the 19th century.

|

| New Gates, Manchester, 1908 |

Overcrowding, back-to-back houses, closed courts where the sun fought to penetrate, and of course a lack of sanitation matched only by parts of the developing world are the stuff of social history.

But the history books and rarely the social observers of the time burrowed deep to offer up the personal stories of those who lived in the cellar dwellings and the one up one down properties, often built in the shadow of textile mills, and iron foundries and bounded by the polluted rivers that ran through the city.

Dr Kay, Frederick Engels and a few foreign visitors did paint a grim picture.

And more revealing is the case notes of Dr Henry Gaulter who experienced the first outbreak of Cholera during the May to December of 1832.

He kept a detailed record of the first three hundred patients he attended describing their physical condition, the onset of the disease and their living conditions but was forced to abandon the exercise as the numbers increased.*

|

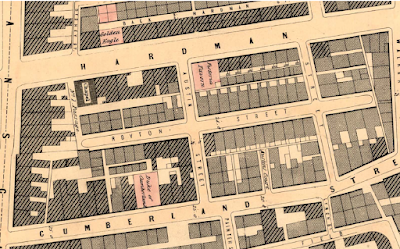

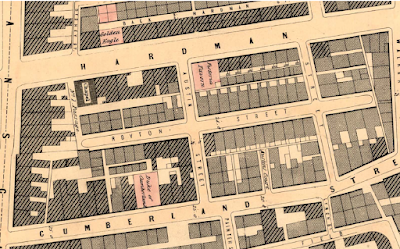

| Royton Street, 1851 |

So, with that in mind I have plunged back into one street off Deansgate in 1851. In that year it was home to 408 people who lived in 46 houses, nine of which were one roomed back-to-back properties, and the remainder, consisted of four rooms with weekly rents ranging from 1 shilling [5p] to 5s [25p].

The street was Royton Street, and history has not been kind to it. It never featured in any of the street directories for the 19th century, and progressively lost its houses and half its length to industrial development and finally vanished under the Spinnyfields project at the start of this century.

There are only two photographs of it in the City’s digital collection, and one of those I think has either been misplaced from somewhere else or is much older than the published date.**

I came across the place by chance a few days ago, wrote about it and planned to move on but the detail is as they say in the detail and so I trawled the 20 pages of the 1851 census and then went back for some of the surrounding closed courts.***

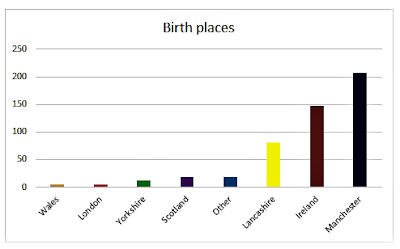

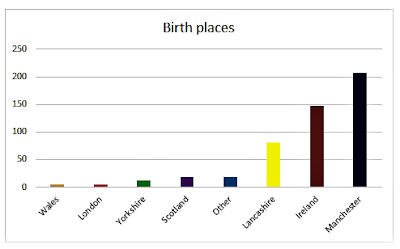

One bit of detail was the presence of a Catholic day and Sunday school in the middle of the street, which made perfect sense given that 36% of the street’s residents were born in Ireland and a cursory look at the surrounding area suggest that this was typical.

|

| Royton Street, circa 1880-1900 |

Nor would the Irish accent be the only one you could hear, for while 50% were from Manchester, there were significant numbers of residents from Scotland, Wales, Yorkshire, as well other parts of Lancashire, seven from London, nine from Cheshire, and even one from Prussia.

Their occupations were as varied as their origins, with a mix of textile workers, four policemen, an architect’s apprentice, and two teachers.

And there were the usual range of skilled trades from carpenters, painters, and glaziers to those engaged in the book and shoe trades, as well as tailors, dress makers, a blacksmith, oastler, and “brick setters.”

But we are in one of the poorer areas of the city, and so here were labourers, house servants, and those on pensions, and poor relief.

To which we can add children, for over a third of the street were young people under the age of 15, and while plenty of these were attending school others by the age of 11, were employed as errand boys, apprentices, and servants.

|

| Birth places of Royton Street residents, 1851 |

The census also records the degree of overcrowding, so our 408 inhabitants lived in just 46 houses made up of 89 households.

Nor does this deliver the true degree of overcrowding. So picking just three houses, which were numbers one, three, and four, together they were home to 38 people.

At number one there were 18, divided into three households, at number three, eight divided into two households, and at number four there were 12 living in three households.

It is a picture replicated across the entire street, and while there were some big families, there were also many lodgers. In total the figure was 72, most of whom were unmarried, were not related, and were occupied in a variety of skilled and non-skilled occupations.

Of the 72, only 11% were from Manchester, with the rest drawn from all parts of the country, with 43% from Ireland.

|

| Age Profile of Royton Street residents, 1851 |

Almost every household included some lodgers, and while there were a few “lodging houses” most families shared their home with people they were unrelated to.

All of which raises the question of how big the houses were.

There were 14 back to back properties which might have had three rooms but equally might have had just two, and the census return is silent on the total number of rooms for these or the remaining houses.

The surviving properties listed in 1901 indicate that they consisted of four rooms, but by then there were only 14 left which leaves the other 32 a mystery.

|

| Royton Street, 1849 |

Nor it appears were there any cellars, recorded on the 1851 census. Now cellar dwellings do show up for other parts of the city, and people are recorded as living in them, so it seems Royton Street was cellar free, or at least, from cellar occupants.

For the curious Royton Street was located between Hardman and Cumberland Streets and its course roughly follows the route of the Avenue in Spinneyfields

|

| In the vicinity of Royton Street, Spinningfields, 2020 |

|

| Occupations of Royton Street residents, 1851 |

Next, I have a fancy to explore some of the families and try to delve into what their lives were like.

Location; Off Deansgate, Manchester

Pictures; New Gates, 1908, m8316, courtesy of Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives, Manchester City Council, http://images.manchester.gov.uk/index.php?session=pass, Spinneyfields, 2020, from the collection of Andrew Simpson and Royton Street in 1849, from the OS map of Manchester and Salford, 1844-49, and Royton Street circa 1880-1900 from Goad's Fire Insurance maps, courtesy of Digital Archives, http://digitalarchives.co.uk/and Royton Street 1951, from the OS map of Manchester and Salford

|

| All that was left, 1951 |

*Gaultier Henry, The Origin and Progress of the Malignant Cholera, 1833, London, & Appendix A, To the Report of the General Board of Health on the Epidemic Cholera of 1848 & 1849, 1850, London

**Royton Street, Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives, Manchester City, http://images.manchester.gov.uk/index.php?session=pass

***Lost and forgotten streets of Manchester .......... nu 95 Royton Street, 1951 https://chorltonhistory.blogspot.com/2022/02/lost-and-forgotten-streets-of.html