|

| Unemployed cotton workers seeking relief, Illustrated London News 1862 |

It’s one of those uncomfortable little bits of history that not everyone was on the side of Lincoln and the North in the American Civil War.

Now I am well aware that the conflict between the North and the Confederacy did not just turn on the issue of slavery, there were profound economic and political differences but for many the war did become a question of the inequity of one man to profit from the labour of another which in Lincoln’s words was part of that flawed idea that

‘You work and toil and earn bread, and I’ll eat it.’*

The Cotton Famine occasioned by the Union’s blockade of the South led to great hardship in the cotton districts of the north west but did not prevent many textile workers supporting the cause of abolition and echoed the earlier petition in 1785 here in Manchester where over 11,000 people called for an end to the slave trade. This amounted to one fifth of the city’s population reflecting working class opposition to the African trade.

|

| From The Liverpool Mercury September 10 1863 |

But not everyone supported the cause of the North and many were of these drawn from the better off sections of our society.

One such was our own Reverend William Birley who had been the incumbent of St Clements from 1842 till he left for St Stephens in Salford in 1859.

William was a keen defender of the rights of the church. While still in the township he had taken on those who objected to paying the church rate and despite ignoring opposition and at times acting in a very authoritarian way he lost. Later he attacked those who wanted to secularise educational provision in the city, and in 1863 came out in support of the Confederacy in the American Civil War.

|

| From The Liverpool Mercury September 10 1863 |

The war had interrupted supplies of cotton and resulted in real hardship in the northwest. Large numbers of unemployed cotton workers and their families struggled and those still in work saw their wages fall.

Opinion was divided over the war with some cotton workers supporting the South in the hope that this would bring an end to the war and a resumption of cotton, others argued that the war was essentially a conflict between free trade and protectionism, but the majority while opposing European intervention supported the North and the cause of emancipating the slaves.

The establishment was also divided. For some like John Bright the war was about Southern privilege and the abolition of outdated social relationships where the

“labourer was made a chattel.” For those connected with the coal and iron industries who were dependant on the North as a market for munitions and railway construction, Northern success was vital to their interests, as indeed it was for the small manufacturers of Birmingham many of whom were engaged in arms manufacture and whose MP was John Bright.

|

| From The Liverpool Mercury September 10 1863 |

But some Liverpool merchants who were relied on the imports of slave grown cotton argued for military intervention on the side of the Confederacy which might also have the advantage of destroying rival American merchant shipping which was almost entirely in northern ports. A view endorsed by one visiting American who felt that some at least in the ruling class would have preferred a divided America because they feared its growing commercial power.

This shouldn’t blind us to those Southern sympathisers, many drawn from the conservative section of society who saw the Southern States as a nation struggling to be free and exercising their right to secede as the American colonies had done a little under a century before.

Amongst this group there was a growing feeling that after two years of war there could be no reconciliation between

“two such belligerents in bonds of amity and mutual benefit”, and that by recognising the Confederacy the conflict would be brought to a conclusion.

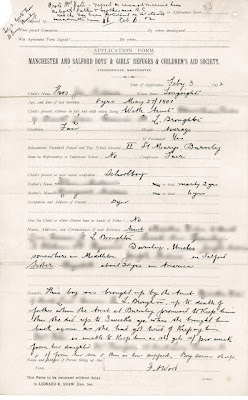

William Birley shared this outlook and was one of those who had joined the Central Association for the Recognition of the Confederate States.** In the September of 1863 along with a large number of “noblemen and gentlemen” many from the northwest he put his name to the call for recognition.

|

| Hardship caused by the Cotton Famine, Illustrated London News 1862 |

Now, Salford along with Manchester had suffered during the famine, and despite the popular view that the majority stoically accepted the privations there were trenchant demands for real help.

As early as June 1862 just a year into the war, a mass meeting at Stevenson Square passed a resolution

“that the relief at present given by the Manchester Board of Guardians is totally inadequate to meet the wants of the people in the present crisis.” ***

While just over a year later workers in Stalybridge rioted after an attempt to reduce the relief paid out and the substitution of tickets usable at local shops instead of money.**** Similar protests spread to the neighbouring areas of Ashton, Dukinfield and Hyde, while in Stockport and Oldham large numbers of special constables were sworn in.

It might indeed be the act of a cynic to suggest that the urge to support the South which might bring an end to the war may in part have been linked to the fear of further disturbances, as much as to the

“interests of our own guiltless suffering people.”

Now I want to fins more of what William Birley thought about the issue, but so far nothing has turned up.

But it is possible to read more about his time in Chorlton, in The Story of Chorlton-cum-Hardy,

http://chorltonhistory.blogspot.co.uk/2012/10/the-story-of-chorlton-cum-hardy-new.html

|

| Statue of Abraham Lincoln in Lincoln Square, © Keith Edkins |

*

It is the eternal struggle between these two principles — right and wrong — throughout the world.

They are the two principles that have stood face to face from the beginning of time, and will ever continue to struggle.

The one is the common right of humanity and the other the divine right of kings.

It is the same principle in whatever shape it develops itself.

It is the same spirit that says, ‘You work and toil and earn bread, and I’ll eat it.’

No matter in what shape it comes, whether from the mouth of a king who seeks to bestride the people of his own nation and live by the fruit of their labor, or from one race of men as an apology for enslaving another race, it is the same tyrannical principle.”

Lincoln speaking in a debate with Stephen Douglas at Alton, Illinois, on October 15, 1858 on what constituted tyranny.

** Recognition of the South, Liverpool Mercury Thursday September 10th 1863

***Watts, John, The Facts of the Cotton Famine page 131 google edition page 152

****The protest began on March 19th 1863, and lasted through till Monday March 23rd, two companies of Hussars had been sent from Manchester and the Riot Act was read, followed by armed patrol of foot soldiers with fixed bayonets. 80 were arrested, Ibid Watts, John, The Facts of the Cotton Famine page 265-276 google edition page 286-296

Pictures; Cotton Famine, in 1863, 10056, 10038, courtesy of Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives,

Manchester City Council, newspaper cutting from The Liverpool Mercuey, 1863, and Photograph of Abaraham Lincoln, © Keith Adkins

Brick works, corner of Longford

Road and Manchester Road, A H

.jpg)