How easy we take writing our name. Even in an electronic age we still sign for things at the door, commit to a legal agreement and perhaps even sign a letter.

All of which made me think again about my family and how such a simple task was denied them.

In the summer of 1848 George Lowe died of TB. He was the grandfather of my grandmother which takes me back in an unbroken line to the mid nineteenth century.

His death plunged a family already on the edge of poverty into real hardship. His wife Maria was just thirty one and she had five children the youngest of whom was just twelve months old.

No records have survived of how they coped, but I know she took in lodgers and the children all went into the textile industry as soon as they could. She had a series of jobs including collecting old linen and later in her later 50s as a charwoman.

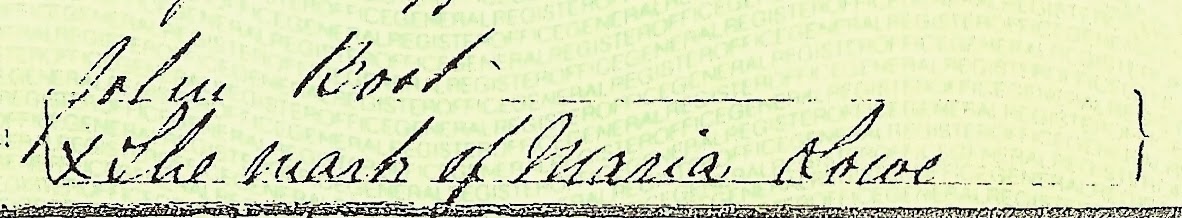

Maria was illiterate as were all her daughters. They each left their mark instead of a signature on official documents. In the summer of 1848 Maria had left her mark on the death certificate of her husband and twenty-seven years later Mary her daughter also put a cross when registering the death of her mother Maria.

All of the girls had each left their mark on their wedding certificates.

As shocking as this seems to us today it was not unusual. In 1840 when Maria was bringing up her daughters over 30% of men signed the marriage register with a mark.

The level of literacy was in part measured by the test of the marriage mark. The authors of the 1851 census on Education fell back on this simple test of how many people were able to sign their name on the marriage certificate as against those who put a cross or mark as a judge of the level of literacy.

They were gratified that the number who put a cross had been falling but felt that it was still not good that well over a third of the population accented to marriage with a cross.

Here in Derby there were sixteen schools in the 1850s ranging from those catering for the well off to those aimed at catholic and Methodist families. But for the rest it would be a National School. These were church schools and provided elementary education for the children of the poor based on teaching of the church.

There were two of these not far from where Maria lived. On Edward Street was St Alkamund’s and on Curzon Street was St Werburgh’s on Curzon Street.

What was offered was fairly basic ranging from reading writing and arithmetic and maybe languages, music, drawing and geography.

The degree to which these were taught varied from subject to subject, and there was a gender split, so while almost all boys and girls were taught the ‘three Rs’, few studied modern languages. Boys were more likely to be taught mathematics than girls while more girls than boys were instructed in industrial occupations.

Nor were these gentle places of education. There was strict discipline and lessons were delivered with the help of monitors who were trained on the job, and much of this would focus on learning by rote. Standing outside the school the passer-by would have heard the repetitive chanting as row by row the children repeated the prepared text.

And if he had strayed inside, hanging from the walls around the room were embroidered verses extorting the virtues of thrift and hard work.

All of which I guess meant there was not much incentive for the girls to attend. And attendance was a problem, so while in the private sector the number of children attending on any particular day was over 90% in public schools which catered for the labouring classes the number it was much less.

For families like the Lowe’s the priority was bringing money into the house and so inspectors often commented that children were away from school and at work.

Not until 1870 was there universal provision for primary school education for working class children and even then it was still possible to gain exemption for even this limited schooling.

Listening to my mother’s experiences of school things had not changed over much by the 1920s. She had attended Traffic Street School as did my great grandmother sixties years earlier. Traffic Street School had been built in 1879 one of the new Board Schools of which many are still around today.

They were grand constructions, well built of brick, with high windows and were warm in winter and cool in summer. By comparison their replacements which went up in the 1950s may have looked better but had plenty of their own problems.

The huge amounts of glass in these new wave schools made classrooms very hot in the summer and cold in winter and presented us with all the distractions due to being able to look out and see the passing world.

But as grand as Traffic School was it did not impress my family. Mother was regularly hit with an ebony ruler across her hands as an infant and during grandmother’s time attendance still only stood at 89%.

Still my mother came out of Traffic Street able to read and write and later wrote plays which were published. The descendants of the Lowe’s went on to University and some have become teachers. How easy it seems for one generation to make a living in a world denied to earlier members of their family.

Picture; the mark of Maria Lowe on the death certificate of George Lowe, 1848, the marriage mark of Maria Lowe in 1864, daughter of George and Maria 1864, from the collection of Andrew Simpson, pictures, of women at work in a silk factory, A Day in a Silk Mill, Penny Magazine, 1843, and Traffic School, 1991 from the collection of Cynthia Wigley

|

| Mark of Maria Lowe, wide of George Lowe, 1848 |

In the summer of 1848 George Lowe died of TB. He was the grandfather of my grandmother which takes me back in an unbroken line to the mid nineteenth century.

His death plunged a family already on the edge of poverty into real hardship. His wife Maria was just thirty one and she had five children the youngest of whom was just twelve months old.

No records have survived of how they coped, but I know she took in lodgers and the children all went into the textile industry as soon as they could. She had a series of jobs including collecting old linen and later in her later 50s as a charwoman.

|

| Marriage mark of Maria Lowe, 1864 |

All of the girls had each left their mark on their wedding certificates.

As shocking as this seems to us today it was not unusual. In 1840 when Maria was bringing up her daughters over 30% of men signed the marriage register with a mark.

|

| Mark of Eliza Bull, 1864 |

Here in Derby there were sixteen schools in the 1850s ranging from those catering for the well off to those aimed at catholic and Methodist families. But for the rest it would be a National School. These were church schools and provided elementary education for the children of the poor based on teaching of the church.

There were two of these not far from where Maria lived. On Edward Street was St Alkamund’s and on Curzon Street was St Werburgh’s on Curzon Street.

What was offered was fairly basic ranging from reading writing and arithmetic and maybe languages, music, drawing and geography.

The degree to which these were taught varied from subject to subject, and there was a gender split, so while almost all boys and girls were taught the ‘three Rs’, few studied modern languages. Boys were more likely to be taught mathematics than girls while more girls than boys were instructed in industrial occupations.

Nor were these gentle places of education. There was strict discipline and lessons were delivered with the help of monitors who were trained on the job, and much of this would focus on learning by rote. Standing outside the school the passer-by would have heard the repetitive chanting as row by row the children repeated the prepared text.

And if he had strayed inside, hanging from the walls around the room were embroidered verses extorting the virtues of thrift and hard work.

|

| Working in a Derby silk mill, 1843 |

For families like the Lowe’s the priority was bringing money into the house and so inspectors often commented that children were away from school and at work.

Not until 1870 was there universal provision for primary school education for working class children and even then it was still possible to gain exemption for even this limited schooling.

Listening to my mother’s experiences of school things had not changed over much by the 1920s. She had attended Traffic Street School as did my great grandmother sixties years earlier. Traffic Street School had been built in 1879 one of the new Board Schools of which many are still around today.

They were grand constructions, well built of brick, with high windows and were warm in winter and cool in summer. By comparison their replacements which went up in the 1950s may have looked better but had plenty of their own problems.

|

| Traffic School, 1991 |

But as grand as Traffic School was it did not impress my family. Mother was regularly hit with an ebony ruler across her hands as an infant and during grandmother’s time attendance still only stood at 89%.

Still my mother came out of Traffic Street able to read and write and later wrote plays which were published. The descendants of the Lowe’s went on to University and some have become teachers. How easy it seems for one generation to make a living in a world denied to earlier members of their family.

Picture; the mark of Maria Lowe on the death certificate of George Lowe, 1848, the marriage mark of Maria Lowe in 1864, daughter of George and Maria 1864, from the collection of Andrew Simpson, pictures, of women at work in a silk factory, A Day in a Silk Mill, Penny Magazine, 1843, and Traffic School, 1991 from the collection of Cynthia Wigley

No comments:

Post a Comment