Now, I came across the line “Their story in our history” in a talk on Chartism and it instantly resonated with me.

We all have our own stories but each feeds into the bigger picture and is particularly relevant in the light of the debate on public statues, and who as a society we choose to remember, and why, and who the history books have chosen to record.

So, when I was at school, history text books were still broadly the story of the “good and the great”, with a heap of Kings, a few nasty people and a sprinkling of clever scientists and inspired generals.

Needless to say, there were few women and those that got on to the pages had walk on parts, causally mentioned as background to the achievements of men.

There were the few exceptions, which included Boudica, Elizabeth 1 and Queen Victoria, and of course Marie Antoinette, but often they were there to show the perfidiousness of men or as with the French Queen a lesson in not saying to a band of starving Frenchwomen “let them eat cake”.*

And while the 1950s saw the beginnings of a change with children’s history books beginning to focus on social history and the lives of ordinary people, a clutch of standard school text books made in the 1970s still peddled a male Eurocentric interpretation of Britain’s past.

But already there was a growing emphasis on working class history and the important contribution made to “Our Island History” by Black, Asian, and other groups.

In many cases it was not that history had forgotten them, it was more that history had just not seen them as important enough to be included in the story.

And that was not an accident, but arose from who wrote the books and the dominant political and cultural outlook of the establishment.

All of which is directly relevant to our history here in Manchester.

So for a century and more, discussion on the Industrial Revolution was dominated by the men who invented the textile machines, developed steam as a means of traction, and designed the canal and early railways, and by extension those who were responsible for the factory system.

Names like the radical Thomas Walker, who spoke in favour of the French Revolution and campaigned for the abolition of the slave trade, and feminists like Annot Robinson in the early 20th century have been largely forgotten, along with figures like Arthur Wharton who “earned the title of the world’s first black professional footballer and is entrenched in Mancunian history after ending his career playing with Stockport County in 1902”.**

Happily the balance is being addressed, so the work of Louise Da-Cocodia MBE, “who arrived in Britain from Jamaica as a 21-year-old in 1955, overcame the overt racism of the time to become the first black senior nursing officer in Manchester, before becoming a dedicated anti-racism campaigner”, has featured in the Manchester Evening News.***

All of which is not stating anything new, but I think does deserve to be revisited. After all, we all have a story and some of them will break new ground while others will fit seamlessly into that big picture.

So, my family history was less about the “great and the good” but about generations of people who lived out their lives against the backdrop of momentous events, which is an outrageous lift from the Yorkshire poet Ian McMillan who said of his parents, “theirs were little lives lived out in a big century”.

But all of them made a contribution leaving me just to draw on that poem, “Who built the seven gates of Thebes? The books are filled with names of kings. Was it the kings who hauled the craggy blocks of stone? And Babylon, so many times destroyed. Who built the city up each time? ………….. Each page a victory At whose expense the victory ball? Every ten years a great man, Who paid the piper?"****

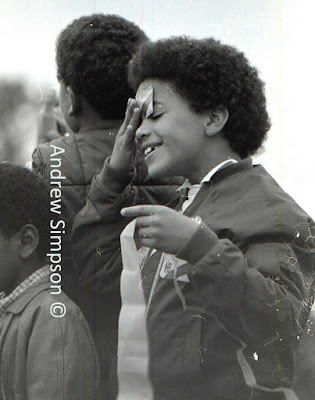

Pictures; Boudica, drawing by J.C.B. Knight, from People in History, R.J. Unstead, Volume one, 1955, and the remaining images from the collection of Andrew Simpson, 1979-2021

* “Let them eat cake”, according modern scholarship it is doubtful she said it

** Black History Month: Exploring Manchester’s influential black athletes, The Mancunion, Manchester Media Group, October 5th, 2018, https://mancunion.com/2018/10/05/black-history-month-exploring-manchesters-influential-black-athletes/

*** Black, brilliant and Manc - the groundbreaking pioneers who helped shape our city, Chris Osuh, Manchester Evening News, October 15th, 2019, https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/five-ground-breaking-figures-black-13760293

****A Worker Read History, Bertolt Brecht

No comments:

Post a Comment